Generation at risk of falling behind in tech skills unless computing education funding improves, report finds

A tenfold increase in computing education funding is needed or the UK risks seeing an entire generation fail to have the technology skills needed for the future, a new report has found.

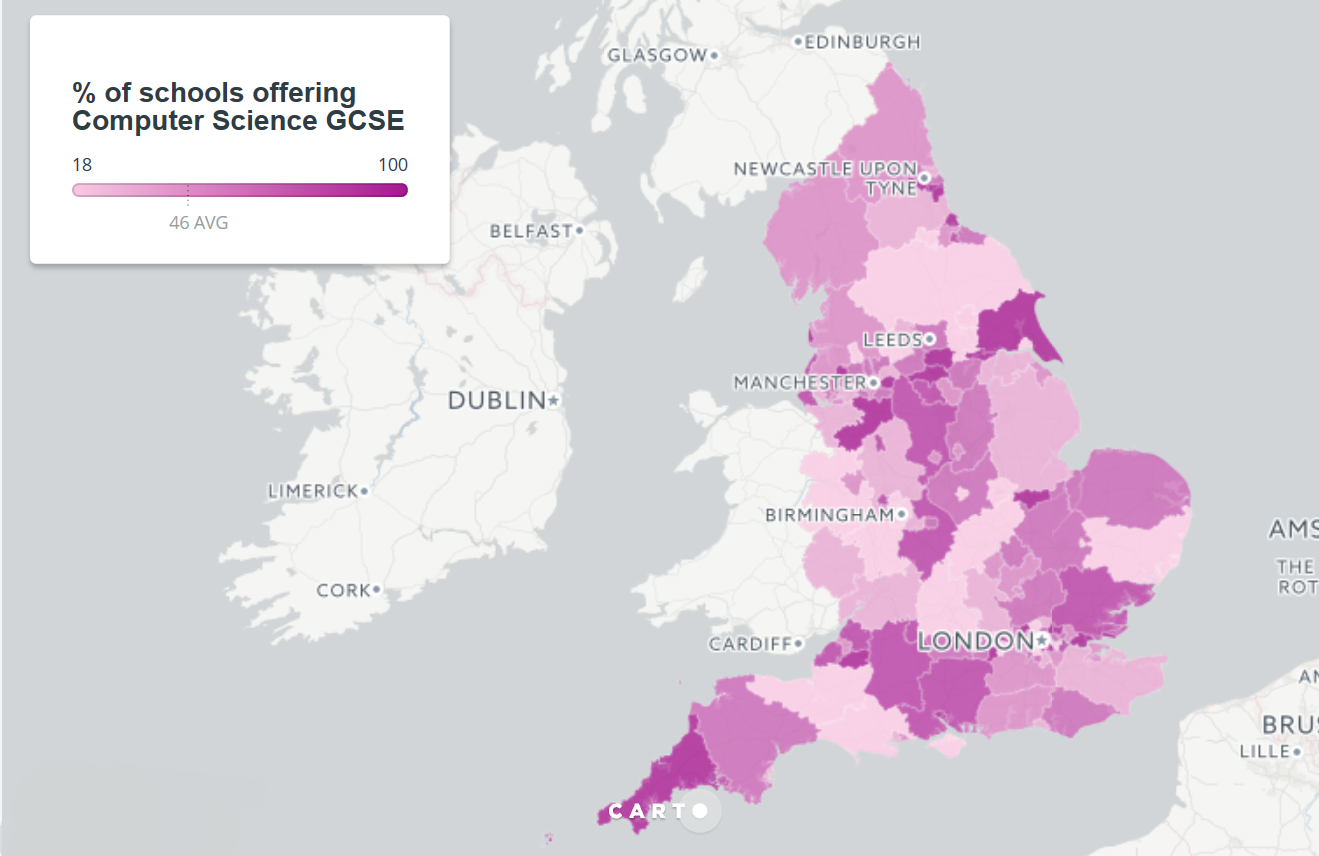

The Royal Society study, which was co-funded by Microsoft, found that more than half of schools in England do not offer a GCSE in Computer Science, leaving many young people without critical experience in coding and programming.

It is estimated that around 85% of the jobs that will exist in 2030 haven’t been invented yet, and these will require skills in areas such as robotics, artificial intelligence and machine learning.

In order to prepare the next generation for advances in technology, the Royal Society, the UK’s national academy of sciences, said more than £60 million needed to be injected into computing education over the next five years – a tenfold increase from current levels. This would give the area the same support as maths and physics.

Cindy Rose, Chief Executive of Microsoft UK, said: “Microsoft is dramatically scaling up its digital skills programme in the UK and we believe now is the time for the Government to do the same. The risk, if we don’t make these investments now, is that too many young people struggle to access new opportunities, and the UK loses its advantage in a world being transformed by technology.”

The report (below), which was also part-funded by Google and led by world-famous engineer Steve Furber, found that:

- 54% of English schools do not offer Computer Science GCSE

- 30% of English GCSE pupils attend a school that does not offer Computer Science GCSE – the equivalent of 175,000 pupils each year, almost a third of the total number in England

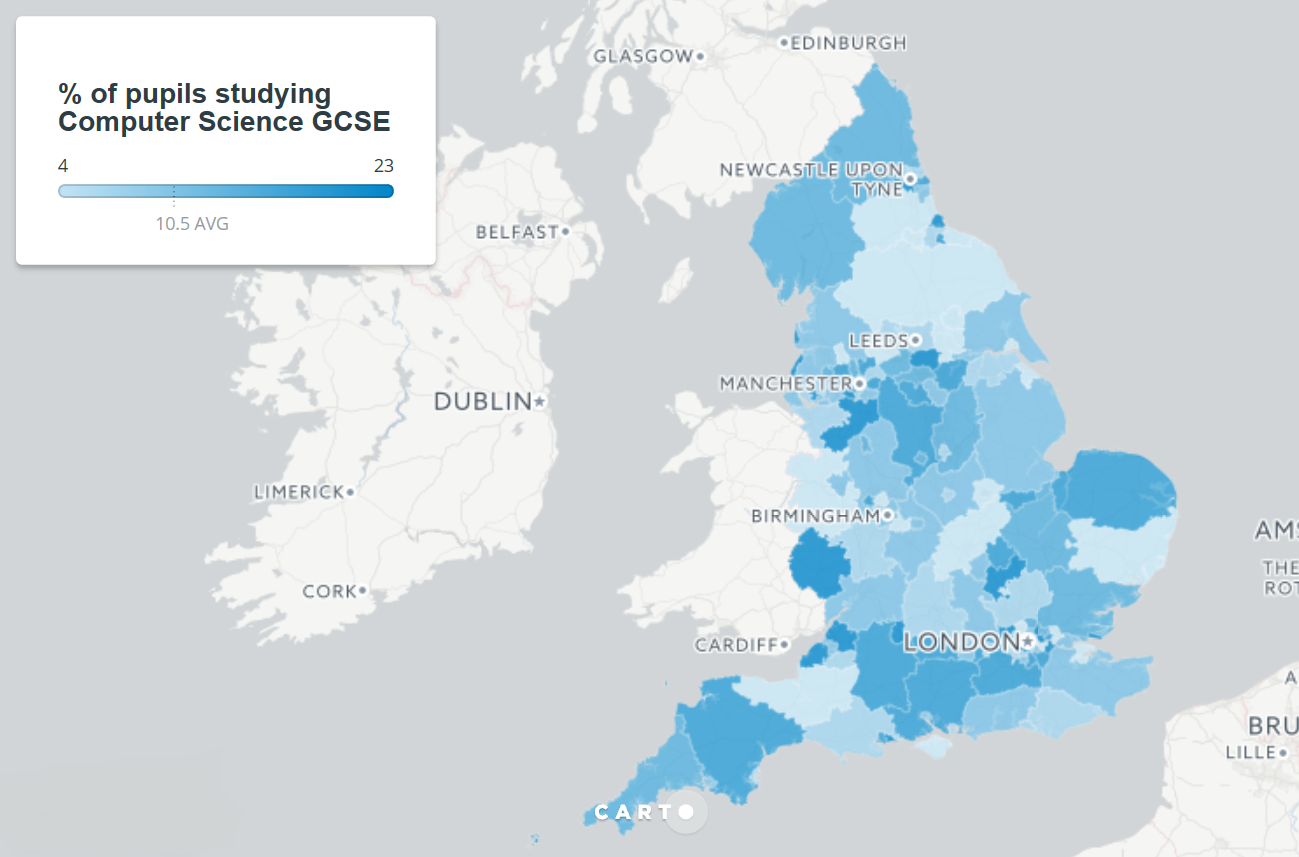

- Bournemouth leads England with the highest uptake of Computer Science GCSE (23% of all pupils), with Kensington & Chelsea, Blackburn and City of London coming last

- England meets only 68% of its recruitment target for entries into computing teacher training courses, lower than Physics and Classics

- Only one-in-five Computer Science GCSE pupils is female

Only 11% of Key Stage 4 students took GCSE Computer Science (62,703 out of a total of 588,000) in 2017. The report also found that more than half of schools in England (2,703 out of a total of 5,135) do not offer Computer Science GCSE at all.

Loading...

Loading...

At local authority level, Bournemouth leads England with the highest uptake of GCSE Computer Science (23% of all pupils at Key Stage 4), followed by Central Bedfordshire (22%), Hartlepool (22%), Knowsley (20%) and Slough (20%). The City of London has the lowest uptake (4%) followed by Blackburn (5%), Kensington & Chelsea (5%), Carderdale (5%) and Rutland (5%).

The report also found that two-in-three schools in Hackney do not offer Computer Science at GCSE level, despite being located near the Silicon Roundabout, London’s tech hub. Nearby Islington only had six out of 14 schools offering the subject.

The Isles of Scilly (100%), Hartlepool (71%), Harrow (67%) and Bracknell Forest (67%) are the local authorities with the highest proportion of schools offering Computer Science GCSE, while Kensington & Chelsea (18%) sits at the bottom of the list, followed by Tower Hamlets (27%), Shropshire (27%), Rutland (29%) and Greenwich (29%).

The report, which was based on a survey, in-depth meetings with teachers and Government data, suggests that part of the problem with computing education is a lack of knowledge about the fast-paced technology sector among staff. One-in-four secondary school teachers surveyed took no professional development activities to enhance their knowledge of computing. The Government allocates just £1.2 million a year to training existing computing teachers, and the Royal Society called on the government to provide enough funding to train 8,000 secondary school computing teachers.

The Royal Society also found that just 20% of GCSE Computer Science candidates were female, falling to 10% at A-level

“For pupils to thrive, we need knowledgeable, highly skilled teachers,” Furber said. “The report paints a bleak picture in England, which meets only 68% of its computing teacher recruitment targets and where, as a result, one-in-two schools doesn’t offer Computer Science at GCSE, a crucial stage of young people’s education.”

Teachers told the Royal Society they are most confident with parts of the computing curriculum inherited from previous Information and Communications Technology courses, and 44% feel more confident in delivering the earlier stages of the curriculum.

Computing teachers are also in short supply, with the government meeting only 68% of its recruitment target for entrants to computing teacher training courses in England between 2012 and 2017. In Scotland, the number of computer science teachers has fallen by 25% in the past 10 years. There is also a shortage of trainees with enough specialist knowledge to teach a technical subject. While there are 65 Physics and 93 Maths teacher conversion courses available, none exists for computing. The Royal Society is calling for government funding on top of the £60 million to set up conversion courses so there is no personal cost to teachers and schools.

Reinforcing previous reports on the gender divide in computing lessons, the Royal Society also found that just 20% of GCSE Computer Science candidates were female, falling to 10% at A-level. There is a similar picture in Scotland, with a 20% female uptake at National 5. Chinese pupils and those from other Asian backgrounds are significantly more likely than white pupils and black pupils to study GCSE Computer Science (12.7% vs 7.5%, 5.5% and 4.1% respectively).

“The rate at which technology is transforming the workplace means that we live in a world where many primary schoolchildren will work in technology-based roles that do not yet exist, so it is essential that future generations can apply digital skills with confidence,” Furber added.

“Overhauling the fragile state of our computing education will require an ambitious, multipronged approach. We need to invest significantly more to support and train 8,000 secondary school computing teachers to ensure pupils have the skills and knowledge needed for the future.”

Microsoft President Brad Smith told the CBI Annual Conference earlier this week that technology skills were in demand in the UK, and companies and that people of all ages needed to acquire the right knowledge and experience.

“It’s clear that 90% of jobs will need new digital skills; and it’s clear that employees don’t have the skills that employers require,” he told hundreds of business leaders at the event in London.

“That starts with bringing new skills into schools, bringing new initiatives like Computing at School, a programme we have been proud to support. It’s a programme that does what needs to be done – create a new curriculum to teach a new subject and provide professional development.”

Microsoft has also launched a programme to teach digital skills to people across the UK, to ensure the country remains one of the global leaders in next-generation technologies.