Microsoft technology can help extend my career, says award-winning artist

An award-winning artist who has been visually impaired for the past 27 years and uses technology to create interactive drawings has said Microsoft products can help extend his career.

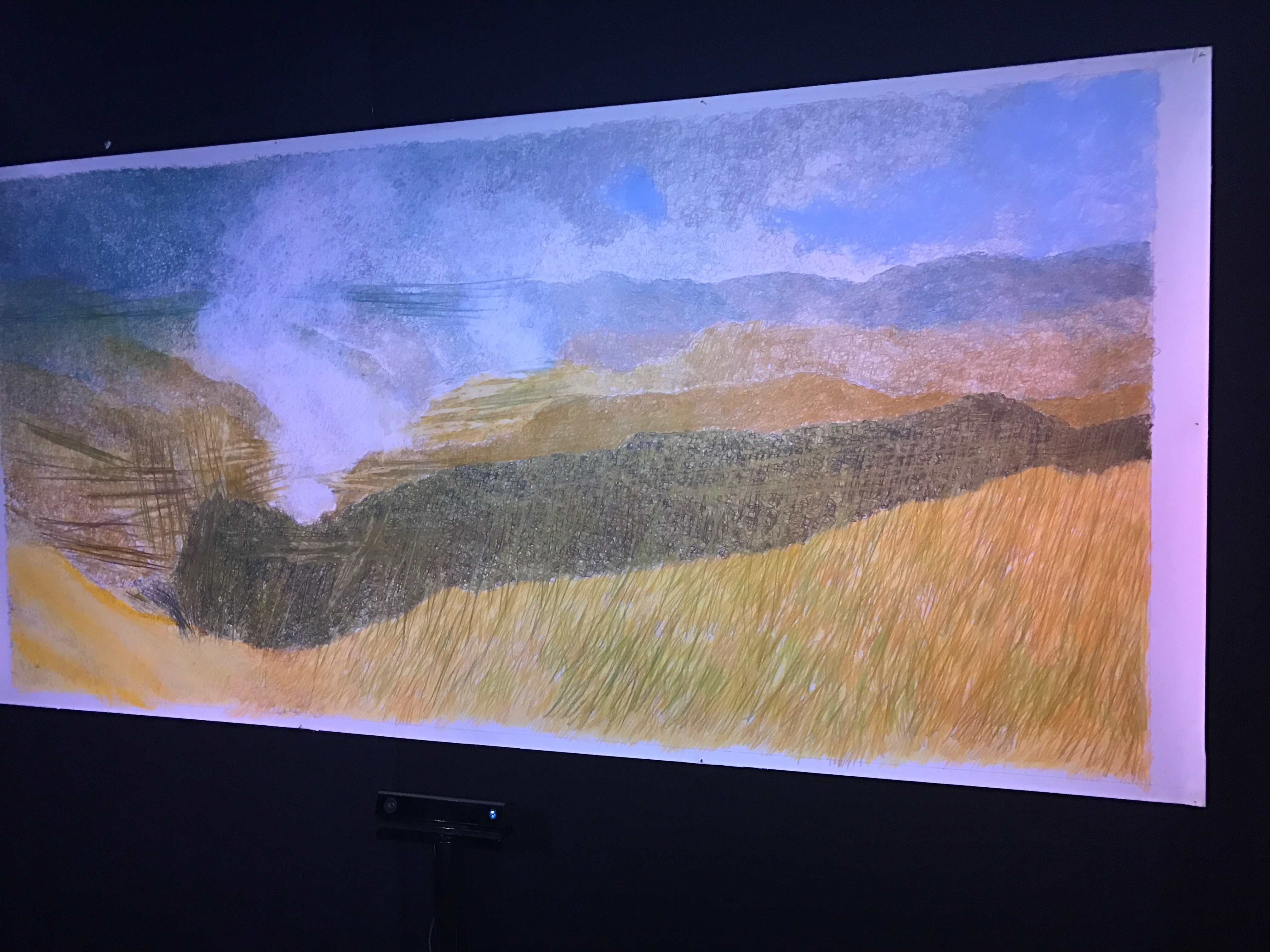

Keith Salmon (above, left, with Microsoft’s Neel Joshi) held a popular exhibition in Edinburgh recently that featured drawings of Hells Canyon, Oregon, set to the sounds of birds, rivers and the wind recorded in the area, as well as the artist himself working.

Three Kinect motion sensors recognised visitors’ movements and allowed them to change the sounds being played in the room depending on where they stood in relation to Salmon’s artwork.

The 57-year-old, who lost most of his sight due to diabetic retinopathy, said he now wants to embrace technology so he can “carry on painting as long as I can”.

“Working with Kinect has been really, really good, because the use of technology to deliver sound in an aesthetic way is essential,” said Salmon, who was born in Essex but now lives in Ayrshire. “I’m going to do more with Kinect to develop the basic concept of using sound with art [and] carry on painting as long as I can.”

Salmon started to explore the use of sound with his two-dimensional art in 2014 after talking about his deteriorating eyesight with a sound engineer, Graham Byron, who lent the artist some equipment.

The Oregon Project exhibition in Edinburgh

A Seattle-based filmmaker, Dan Thornton, then decided to make a documentary about Salmon, and put him in touch with two friends at Microsoft – Neel Joshi and Meredith Ringel Morris – who were looking into using Kinect as an audio tool to help people with low levels of sight to better interpret 2D images.

Joshi, a Senior Researcher at Microsoft Research, said: “It started as a research project, mapping visuals to sound using a Kinect. We did some studies with people who were blind and found there were some benefits, but we knew it needed to be thought of as an integrated artistic experience.”

Joshi, a Senior Researcher at Microsoft Research, said: “It started as a research project, mapping visuals to sound using a Kinect. We did some studies with people who were blind and found there were some benefits, but we knew it needed to be thought of as an integrated artistic experience.”

Salmon flew to Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond, Washington, to work on the project, making trips to Oregon to sketch the landscape and record sounds.

“We spent a long time sketching and recording and taking photos and film,” he said. “I then went back to Scotland and sorted through what we had, beginning a very lengthy process of creating three large pastel drawings of the Hells Canyon landscape and working with Graham to mix 54-minute-long soundtracks [for the exhibition]. Meanwhile, Neel and Dan were in the US working on the delivery system – how the Kinect would work when people moved in front of the drawings.”

Salmon, who won the Jolomo Award in 2009, subsequently completed three pieces, each measuring eight feet by four feet. Initially they were displayed to much acclaim at the nine-day 9e2 event of installations and performances on art, science and technology in Seattle, before Salmon and his colleagues moved them to Edinburgh.

Three Kinects, one under each drawing, “saw” people as they approached and changed the sounds emitting from speakers depending on how close they got.

“When you stand back, the sounds [are] from where we recorded them in Oregon – one is from almost 3,000 feet down in the base of the canyon next to a river, birds in the trees, wind blowing. When you move up close, you lose the landscape and just see an abstract set of marks, so we recorded the sound of me making the marks; you become immersed in me creating the drawing in my studio,” Salmon added.

The Oregon Project exhibition in Edinburgh

Joshi, who has produced an academic paper on the project, said: “Regardless of whether you had full vision or no vision, you could get something out of it. We didn’t want to create something that was only for someone who was blind.”

That view was echoed by Salmon, who said The Oregon Project could revolutionise museum experiences for people with low levels of sight – “When you go into a museum, it can be a nightmare. There’s very low levels of light and ropes that can start alarms. Exhibits can be almost impossible to access. It would be great to think that in a few years, you might go to a national museum or art gallery and this technology would be there as part of the experience” – but was there for everyone to enjoy.

Salmon said: “This isn’t just a gimmick, a clever piece of art, it can be a way to develop new forms of work.”